Mostly true:

a fifth of university graduates

in Korea are unable to find a job

On November 18, 2021, the news agency “Red Spring” published the article that considers the problem of employment of Korean university graduates. The author of the article is not specified.

This article is based on materials of Korean news agency Yonhap and the primary source, the results of the report of Korea Economic Research Institute (hereinafter – KERI). The article also contains tables comparing statistical data from across South Korea and member countries of The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (abbreviated further as OECD).

We asked experts and analyzed other research papers in economics that helped us to confirm the accuracy and reliability of the article. However, it seems that the author misinterpreted the economic terms ignoring errors that may happen during the process of translation and making the claim false in a way.

The educational environment in South Korea is now among the ranks of advanced countries. According to the report of the BBC, analyzing math and science exam scores, South Korea ranked 3rd after Singapore and Hong Kong in 2015.

The US News published the 2022 Best Countries for Education rankings which are drawn from a global survey of more than 17,000 people. The Republic of Korea ranked 19th among 85 countries.

Nevertheless, the shadowy facet of South Korea’s education system is the high competitive and the fact that a lot of employees find job conditions unsatisfactory.

It is mentioned in the research paper “Investing in Youth: Korea” published by OECD. The Koreans choose colleges and universities and often invest a lot of time and money in qualifications and certificates and can nonetheless find themselves relegated to unstable and unsatisfactory employment.

In the article, the news agency outlet claims that 20.3% is the percentage of university graduates who have not found a job. However, there is another meaning which is explained by KERI. According to report, 20.3% indicates the percentage of the economically inactive population that is not equivalent to the author’s thesis in the article.

The economically inactive population

According to the International Labour Organization definition, a person is outside the labour force if he or she is not part of the labour force, meaning he or she is neither employed nor unemployed.

The KERI report explains the following:

The economically inactive population is people over the age of 16 who do not want to work, or do not work in agriculture, or those who are unable to work. This article analyzes the inactive population aged 25 to 34 years.

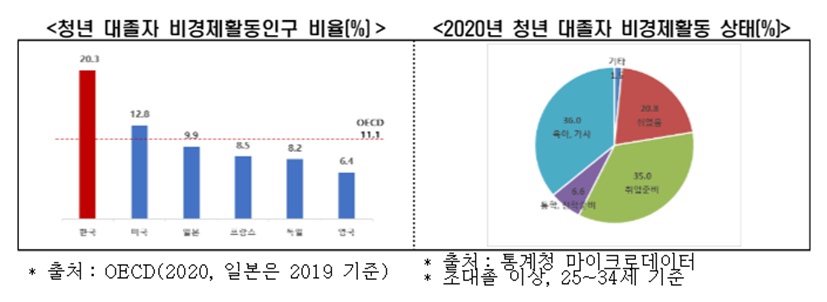

The charts which are below visualize:

- The percentage of the economically inactive population among university graduates (%). Source: OECD (as of 2020)

- Activities of non-economic activity of university graduates in 2020 (%) aged 25-34 years.

The percentage of the economically inactive population in the Republic of Korea is truly 20.3%. These data are confirmed not only by the KERI report but the official statistics of the OECD database[1]. However, the activity states of people who are economically inactive vary. This 20.3% might those who did not initially look for a job. According to the article of the Korean news agency Yonhap, the author Kwon Hee-won writes that if we look at the activity states of the economically inactive population among young people who graduated from university last year (those who do not work due to lack of ability or desire to work among the population over 15 years old), it turns out that 3 out of 10 are job seekers, and 2 out of 10 are resting.

Anna Abrosimova holds Ph.D. of Economics and is a professor at The Institute of Economics & Entrepreneurship and that’s her opinion about the matter:

This economic situation is relevant for absolutely all countries. In Korea, you can see changes in indicators and an increase of the economically inactive graduates. An important point here is not to confuse the two different statuses: because “they are not looking for a job” does not mean that they do not have another activity that could potentially generate income. In addition, it is necessary to find the factors influencing the choice of work in Korea.

The labour force status of economically inactive population is different from another one – unemployed population. In the article, the author mentioned only that part of graduates who were job seekers but fail to find the job. We know that people who are jobless, but available and are looking for a job are called as unemployed, and consequently we see mismatch of economic terms.

In the employment statistics youth are defined as persons ages 15 to 24. The OECD publishes employment rate by the age group. Employment rates are shown for four age groups:

– people aged 15-64 (the working age population);

– people aged 15 to 24 (those just entering the labour market following education);

– people aged 25 to 54 (those in their prime working lives);

– people aged 55 to 64 (those passing the peak of their career and approaching retirement).

However, the KERI report points that the OECD sets an age structure of 25-34 years for people who have received higher education. Percentage of economically inactive people in this research is studied only for people aged 25-34 and only for a tertiary education level.

Thus, the economically inactive population in the Republic of Korea for 2020 is 20.3%. It includes aged 25 to 34 years who, according to certain factors, are not initially interested in getting a job or those who do not have the opportunity to work.

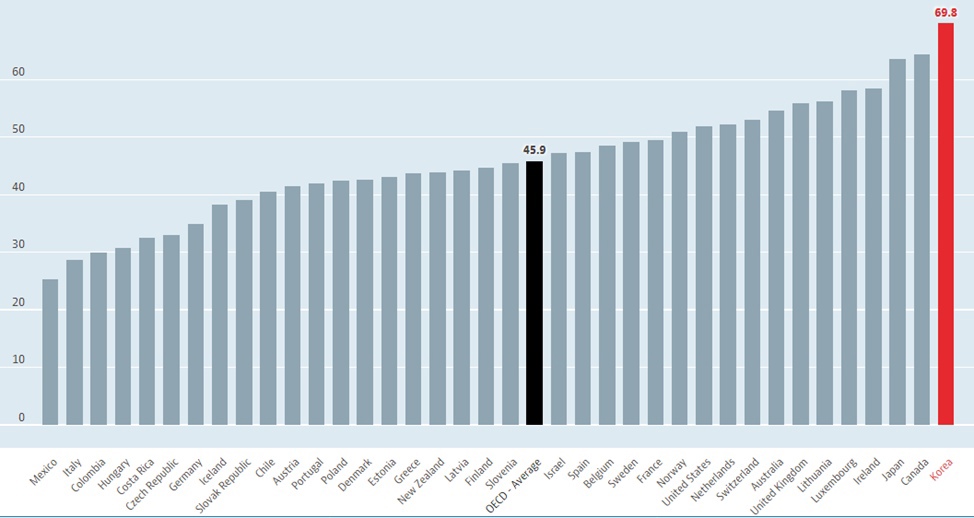

Employment rate in South Korea and OECD countries

The author of “Red Spring” news agency also claims that the employment rate in South Korea among young people aged 25-34 is much lower than in the UK, Germany and Japan, and Sweden, Turkey, Greece, Italy, Costa Rica and Colombia has lower rates than Korea.

In the KERI report, the statistics are presented in the charts. We translated it and found the incorrect information.

The employment rate for South Koreans aged 25-34 with university diplomas came to 75.2 percent in 2020, the 31st lowest among 37 comparable OECD member countries. However, the chart also shows countries with lower indicators. According to this, Spain, Costa Rica, Colombia, Turkey, Greece and Italy had lower rates. Sweden which is mentioned by the author of the article ranks 4th here.

A mismatch between university graduates and job openings

In the article, the author writes that, according to KERI, the reason for the low employment of young people in the labour market is the mismatch between the specialties completed by graduates and those vacancies that employers can offer.

It is worth noting that education in the Republic of Korea is at a high level. According to the results of a study of the OECD database in 2020, Korea has the highest rate in terms of the number of people aged 25-34 who completed the highest level of education. It also had the first place in 2021.

The director of Economic Policy at Han Kyong-yeon, Choo Kwang-ho said that the education of young people in Korea is at the highest level, but human resources are inefficiently distributed.

A researcher of the Korea Development Institute (KDI), Kyuongsoo Choi, writes in a research report that the unemployment rate in Korea among Youth is increasing due to the slow emergence of professional and semi-professional jobs. He says that choosing a job for Korean graduates means choosing a career, so they take irregular positions in large companies, preferring to expand their portfolios for future opportunities instead of taking small but high-paying jobs.

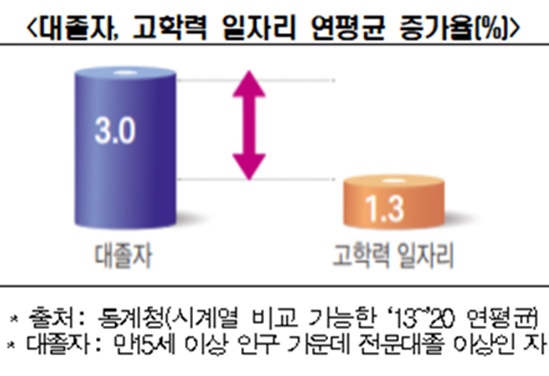

We can agree that one of the reasons of low employment of graduates is a demand–supply imbalance in the labour market. Korea has the highest share of graduates. High competition in the labour market and the unwilling of Koreans to get jobs that do not correspond to a high level of qualification requires an increase in the number of jobs, since there are currently not enough. The KERI report also shows statistics indicate that the number of university graduates expanded at an annual average rate of 3 percent between 2013 and 2020, while and the number of jobs for university graduates and over gained 1.3%.

Conclusion

In South Korea, university graduates have to make efforts to find a job that matches their qualifications and working conditions they want. Therefore, the author’s statement from the article of Red Spring about the indicators causing low youth employment is true. However, despite the fact that the share of the economically inactive population may include people who are already desperate to find a job, there are other reasons why they are not part of the labour force. In addition to the fact that high competition is the cause of youth unemployment, it is worth mentioning that many Koreans do not want to work or do not have an urgent need to earn after graduation.

Thus, the author’s thesis divides the percentage rates presented in the KERI report, focusing only on the part of young people who could not find a job. Therefore, we can characterize this material as mostly true.

AUTHORS

© Sabina Vagapova, Eva Miheeva, Anna Sadovina.